Lost 1947 Sci-Fi,—atomic-age anxieties

“I have the report of the Montana crash . . . Out of the scorched and twisted wreckage the authorities picked certain remains of a human being. This human being must have been a child . . . It remains to be worked out.”

Researched by James Hall

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

My dad and I recently came across Gerald Kersh’s prophetic short story “Note on Danger B,” published in “The Saturday Evening Post” on April 5, 1947, and illustrated by Geoffrey Biggs. This rare, largely forgotten gem of postwar speculative fiction appeared just two months before the Kenneth Arnold sighting and three months before the supposed Roswell event. Its title and publication context suggest a cautionary tale exploring scientific and military peril—true to Kersh’s talent for psychological tension, dark satire, and atomic-age anxieties.

This April 1947 narrative presents a flying “Ace of Spades,” temporal-speed anomalies, and a secret industrial contractor serving the government—predating public discussions of such themes.

The story emerged when science fiction was infiltrating middlebrow culture, reflecting growing public curiosity about technology, secrecy, and existential dread. Although not widely accessible today, it has resurfaced in anthologies such as “The Brighton Monster and Others” (1953) and “The World, the Flesh, & the Devil” (2006), preserving its relevance as a document of its era’s imaginative response to new dangers. James Hall

Now Here Is The Story:

“Note on Danger B”

By Gerald Kersh

Illustrated by Geoffrey Biggs

Intro by Gerald Kersh:

The terrifying thing that happened inside the jet-propelled plane was too fantastic for anyone to believe . . . except the man who lived through it to describe the menace he found lurking in the stratosphere.

Doctor Sant says that he and Captain Mayo exceeded 1000 miles an hour in the jet-propelled F.S.2 on April 11, 1945. The fact has yet to be confirmed.

Danger A was established as a real danger in October, 1945. Sober scientists have not yet fully acknowledged the existence of what Doctor Sant calls Danger B.

The suppressed pages of the Sant Report are curiously interesting. however. They bring back into memory one of the most remarkable theories ever put forward by an established mathematician. The mathematician was Berliner, who died in 1910. The work to which Doctor Sant references is formidably entitled: Living Cells And Their Relation To Time; With A Note On Time So Far As Time Is United With Velocity And Space. It was written by Berliner, revised and indexed by Wasserman in 1911, and published by Frischauer in 1912 in Vienna. Only 350 copies of this book were printed. It is extremely rare. There is a copy in the library of the British Museum, and another in the Bodleian Library. I know of no others. Gerald Kersh

The story begins:

After two years of departmental wire pulling and patient waiting, I have been granted permission to publish the suppressed pages of the Sant Report which the War Department filed away as “Secret” in April 1945. This is the document of which General Branch said, “It surely must be the most astounding thing of its kind that ever has been or ever will be written.”

By “of its kind,” General Branch meant “of the official kind, written by a responsible scientist in the proper language, and formally handed in to the proper authorities.”

For the report was written by Doctor Sant. It deals with the first flight of the jet-propelled F.S.2, and with two of the dangers that threaten the flier who wants to cover too many miles a minute. He refers to them as Danger A and Danger B. Nobody had thought of them until Doctor Sant wrote that brief, brusque and utterly sensational report. The possibility of Danger B. The War department kept it quiet, at that time the fact was not established, and seemed indeed, unverifiable.

But it now appears that some crumbs of evidence scraped out of the smoldering wreckage of a machine that crashed in Montana have given the experts cause to think again.

Danger A has to be overcome when the flier catches up with sound and touches 700 miles an hour. Then your hurtling metal machine crushes the vague atmosphere into something hard—much as a manufacturing chemist’s press squeezes fine, loose amorphous powder into an aspirin tablet. In effect, you put up a brick wall of compressed air and smash yourself in knocking it down. And so a shower of scorched and twisted metal comes back to earth.

This was to be tragically demonstrated by just such a catastrophe over England, 1947. Doctor Sant had seen the possibility of such mishaps as long ago as 1933, when he had already evolved a sound theory of jet-propulsion and had even made a blueprint of a workable jet-propelled machine which he called F.S.1. The letters F.S. stood for Flying Spade simply because the outlines of Sant’s machine, in 1934, were reminiscent of the ace of spades. These outlines were modified by 1945, by which time—having been lucky adroit enough to get moral, financial, technical, and other support—he was building F.S.2, in which he and Captain Mayo made a test flight.

F.S.2 looked like the head of a harpoon; it had an appearance of keenness and complete efficiency. A fabulously wealthy motorcar manufacturer whose name I may not mention financed the experiment, with the approval of the War Department, and so F.S.2 was put together secretly somewhere in Nevada. It was finished before the end of 1945—the necessities of war had mothered inventions which made this possible.

The F.S.2 took off on its first serious flight on April 11, 1945. This happened to be Doctor Sant’s fifty-second birthday—a fact difficult to believe. In spite of his white hair, Doctor Sants looks like a well—preserved athlete on the right side of forty; an athlete of the agile, slender kind—a runner and a jumper. Yet he boasts that he has not taken a stroke of exercise in thirty-five years. He attributes his vigor and his youthful appearance to the fact that he never drank alcohol, never smoked cigarettes and never got married, but lived only for his work. “I gave myself completely to work,” he says. “That is as good a way as staying young. Friends, enemies, wives and children—they just weren’t for me. They’d have torn me to bits like four wild horses. Life has marked me up, because I haven’t had time to live it. I’ve just worked all the time. Although” he adds, laughing, “work can mark you up a bit, too”—and he points to his nose, which is very badly broken. He did not get this injury in any romantic way; in 1943 he was hit by a piece of flying steel when something exploded in his laboratory. “Still, it doesn’t cut half as deep or hurt half as much as a sad man’s wrinkle,” says Doctor Sant.

Captain Mayo was born in Pasadena in August, 1919. He is one of those flying prodigies peculiar to our time, for whom the whirling earth is too slow and boggy. He could take a car to pieces and put it together again before he was fifteen years old. Above all things he loves speed—speed for speed’s sake. He resents the tyranny of the law of gravity; he wants to get away from everything that clutches man’s feet. Therefore he, too, is still unmarried. In his business it is better to be a bachelor. The perils of mad speed in the upper air are fantastically incalculable—as Doctor Sant’s nightmarish report clearly indicates.

I should say in passing, that Doctor Sant overcame Danger A by a bold—almost foolhardy—application of what he called the gun-and-candle principle. This principle is as old as the hills. Fire a soft candle from a smooth-bore gun, and the power behind it will send that candle right through an oak plank. Similarly, a fine needle embedded in a cork and struck smartly with a hammer will pierce a tough bronze penny—a needle that would snap if you tried to push it through a fold of canvas. Furthermore, Sant did not attempt to achieve his highest speed until F.S.2 was up on the lower curve of the stratosphere, thus eliminating some of the danger of air resistance.

Sant and Mayo took off on April 11, 1945 at nine o’clock in the morning. They were back on the airfield about fifty-five minutes later. Something had gone wrong with their speed indicator. This instrument was designed to record speed up to 1000 miles an hour. It was broken. Doctor Sant says that it broke when F.S.2 reached the speed of 1250 miles an hour or thereabouts. I state the figures exactly as they are recorded in the report. They are questionable, because the indicator stopped working. In certain quarters there is no doubt at all that Sant and Mayo on that occasion traveled faster than any human being has ever traveled before.

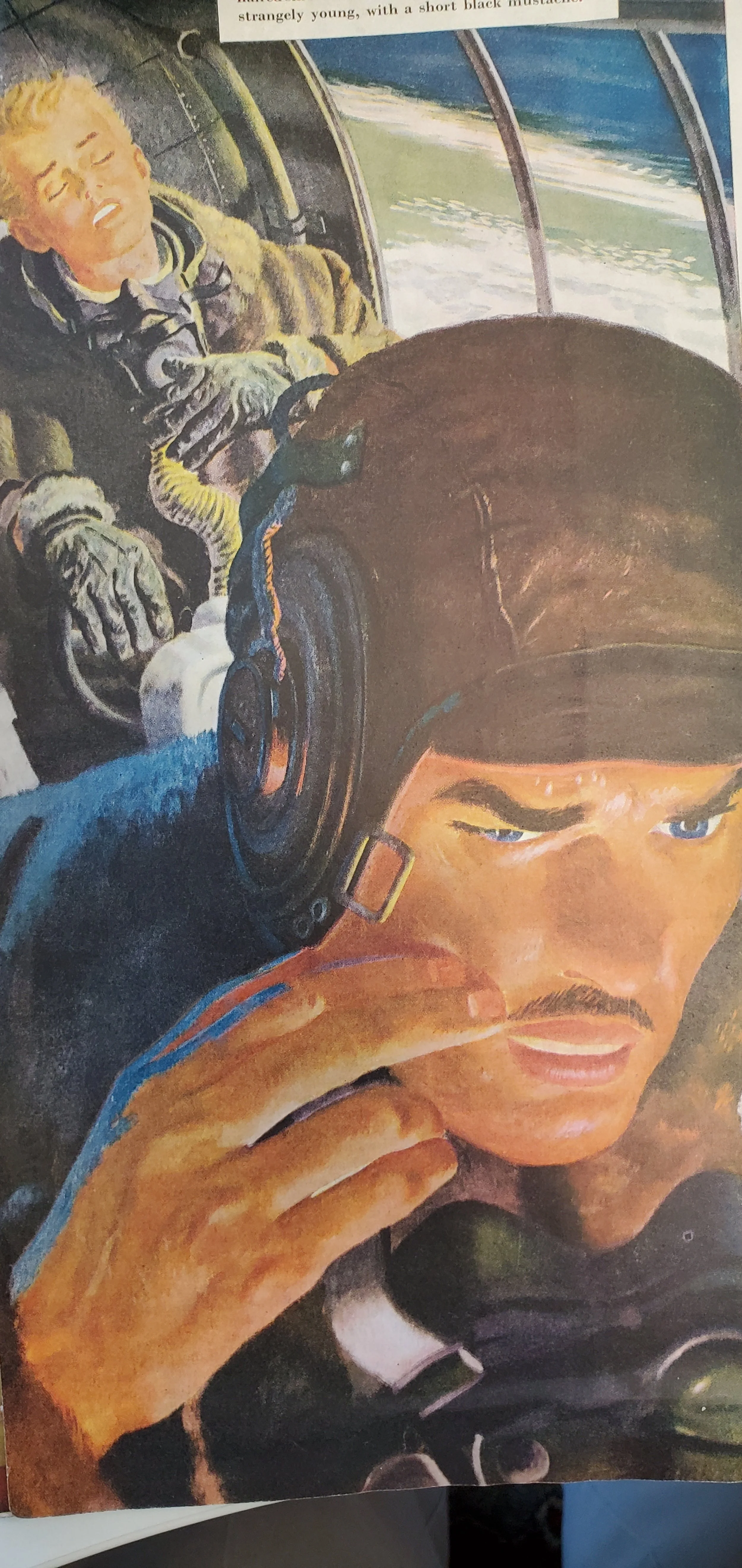

Illustrated by Geoffrey Biggs

Doctor Sant was proud and, for him, excited.

Captain Mayo was ashamed; he had blacked out, or become momentarily unconscious, as they turned to come back. He wanted a cup of coffee. But to everybody’s astonishment, the first thing that Doctor Sant said when he set foot on the ground was, “Has somebody got a mirror?”

Somebody had a mirror. He looked at his reflection; explored his broken nose with anxious fingers; said, “Ha!” and went to his office, shouting “Berliner! Berliner! Berliner!”

He stayed there for three hours, reading a book and making notes on a lite blue scribbling block.

That evening Doctor Sant wrote his report. The War Department cut out every reference to Danger B.

Bur now, after two years, the ban is lifted, and I may give you the substance of what Doctor Sant wrote. In the original document, Doctor Sant quoted certain figures and formulas which it is at present pointless to print. The formulas, particularly, contribute nothing to the story as it may be understood by the man in the street, for whom this is written, Doctor Sant’s figures take us into the higher mathematics—into the esoteric mathematics that made headlines when Einstein first made news.

Anyone who understands the theory of Berliner—and only five men in the world can make head or tail of this theory—may workout for himself exactly what Doctor Sant was driving at.

But any schoolboy may grasp the broader aspects of the suppressed part of his report, dated April 11, 1945, handed in on the morning of April twelfth.

Doctor Sant said:

. . . I am aware that the failure of the indicator discredits my claim to having traveled at over 1000 miles an hour. Nevertheless, having tested every instrument with the utmost care, I am convinced that the indicator broke down because of the excessive strain imposed upon it by the speed achieved by F.S.2. I cannot support this claim, yet I am satisfied that Captain Mayo and I, on this occasion, broke every existing speed record. Similarly, there is no way in which I can confirm Danger B, which I believe to be a real danger.

For the sake of investigators in the near future, who will take up F.S.3 and F.S.4, I believe that it is my duty to relate events as I experienced them.

I had overcome Danger A, and—according to the indicator—had touched 875 miles an hour. The coughing and roaring of the jet has died away, and there was a peculiar quiet. If it had not been for the flickering of the indicator needles and the vibration of F.S.2, it would have been easy for me to convince myself that we had stopped moving and were hanging perfectly still in space. But the indicator told me that we were traveling at 875 miles an hour, then 900, and finally 1000 miles an hour.

As the needle touched the last mark on the dial and agitated itself as if it were trying to push away beyond, I felt an extraordinary sense of lightness. I can make this sensation clear only by saying that I felt suddenly younger. I asked Captain Mayo how he was feeling, and replied, “I feel as if this is just a dream.”

I did not look round at that time. F.S.2 is designed so that it may be duly controlled. I, sitting in front, kept my eyes ahead. But a second or two later my eyes filled with tears, as though I had been struck on the nose. Indeed, my nose at that same moment began to throb and ache.

It had throbbed and ached in a similar way shortly after the septum had been removed in the operation that followed the explosion in my laboratory in 1943.

The throbbing and the ache brought this very vividly back into my recollection. Two or three seconds later, instead of this throbbing, I was aware of a strange, shocked numbness, which, even as I became aware of it, went away.

Something compelled me to loosen my mask for a moment and feel my face. First of all, I touched my nose. It was no longer broken.

It occurred to me, naturally, that this was an illusion such as one may be occasionally subject to at certain heights and under certain pressures.

I spoke to Captain Mayo and asked whether he was alright. He said, “Well, I guess I am.” His voice sounded uneasy, and I asked him if he was sure that he was alright.

Captain Mayo did not answer, and so I turned my head and saw him touching himself uneasily and looking at his hands in a bewildering way.

“Too much oxygen? Too little?” I asked. Captain Mayo replied, “I just feel a bit strange.” I said, “We’ve touched a thousand miles.”

“How did we ever get to do that?” he asked, and his voice was very different. All the authority was gone out of it. Then he uttered a sharp cry and said, “My arm! My arm!”

I looked and saw that his left forearm was dangling. It would have been hanging vertically downwards but for the support of the layers of sleeve that enclosed it.

Even as I looked, Captain Mayo’s arm straightened out with a jerk, and at this his whole manner changed. He squared himself and said, “This is it, Bill! Let them have it!”

And then I remembered these were the words of Captain Mayo is reported as having said when he was flying in France in 1942 and, his arm smashed by flak, took a Marauder into a suicide dive from which he emerged alive and unhurt—except for his shattered arm.

I felt remarkably light and cheerful. In an indefinable way I felt different. I began to remember things which had faded out of my memory long before—things trivial in themselves, yet somehow important at that moment.

The needle of the indicator had gone limp; yet I am sure that we were moving at 1000 miles an hour at least. Only the vibration of the F.S.2 indicated to me that we were moving. But the speed indicator being dead, I had a strange and unreasonable sense of having gone out of this world. Strange, illogical anxieties crept into my mind. I said to myself, Tomorrow, at about eleven o’clock, I must see what has happened to Ledbetters’s castings. And then I remembered that Ledbetter was in Canada and that he had not made a casting for me since 1938, when my hair was still black. I was unable to resist the impulse to peel my glove away from my cuff.

There was a reason for this. In the summer of 1938, a week before Ledbetter had finished my castings, I was rather severely bitten in the right wrist by a schnauzer dog belonging to my sister. This bite had worried me then; I had feared infection and disablement at a certain operative moment.

There was no disablement and no infection. The marks of the dog’s teeth have faded, so that now they are scarcely visible. But as I looked I saw four half-healed lacerations in the skin of my wrist grow angry and inflamed, and then, in a split second, change so that they became bleeding red wounds and then, in a flash, disappear. And I observed, also, that the hair on my wrist, which, since 1937, has been gray, was black.

I felt my nose. When I took off with Captain Mayo, it was smashed flat and boneless, as it is at present. Yet under my fingers then, it was hard and straight as it had been before it was broken. I uncovered my face and looked at my reflection in the glass-covered dial of one of the instruments in front, and I saw that my face was different. I have been clean-shaven since 1936, and gray-haired since 1938. The shiny glass reflected my face, strangely young. The nose was un-unbroken, and under it I saw a short black mustache,

I have not had a mustache since late in the autumn of 1936, when I shaved clean at the request of a young lady whom I have since all but forgotten. As I looked at the incredible reflection of myself, I found myself wondering what this young lady was doing, and reproaching myself because on her account my mind was so easily taken away from the work upon which I had been so keenly concentrating. It was as if I had slipped back nine years in time. I did not like that.

And still we might have been motionless in the sky.

It is fortunate for Mayo and for me that I turned just then to say, “Tell me, how do I look?”

Captain Mayo was apparently unwell. He is, as the records show, about twenty-six years old, six feet tall, and one hundred and seventy-two pounds in weight. When I turned, just then, I saw him as a boy of about sixteen, ludicrously little, in a heap of heavy, complicated garments that were slipping away from him as he became smaller, line by line.

His mask had slipped. His eyes were closed and his mouth was open. He was saying, “Mother! Mother!”

I reached back to shake him. As I did so, one of his gloves slipped off, uncovering the hand of a little boy.

It is fortunate that I turned when I did. Another fifteen minutes might have put an end to everything. I knew in those few seconds that what Berliner had dreamed was basically true, concerning man in relation to time and velocity. Traveling at a certain speed, presumably in a given direction—I hesitate to specify or to say that it is necessary to specify direction—a man touches one of the grooves along which time travels.

Berliner maintains that time passes man, and not that man is swept along by time. In common with certain others, I used to laugh at this. Now I have modified my opinion.

In only a few minutes, at that speed, Captain Mayo and I were back ten years in time.

I am thankful that this occurred to me. If the principle of F.S.1 and F.S.2 had not been clear in my mind eleven years ago, we must have crashed. In a few minutes more I believe that we should have gone back to the period when F.S.2 was nothing but a theory. I believe that I should have found myself in that machine like a child in a nightmare isolated at a great height. And then there would have been a sickening sensation of falling, falling, falling! And behind me under those heavy clothes there would have been a baby crying.

Already there was a certain dreamy wooliness in my head. I was experiencing something I had experienced somewhere between sleeping and waking many years before. I knew exactly in what machine I was flying. But I no longer knew what made it what it was. It seemed to me that I was rushing back, faster and faster, toward the eleven-year-old deadline behind which I should be lost forever, The memory of the Christmas of 1934 was very vivid in my mind.

We were traveling faster and faster. My only hope was in a quick turn. Then, it seemed that I was in F.S.1. Even that was fading. Nevertheless, I managed to turn. I saw my face getting older. I felt the impact that broke my nose, and then the familiar ache and throb that resulted. Looking behind me, I saw Captain Mayo stirring uneasily. He had filled his clothes. In a minute or two he became conscious. He told me that he had a blackout, as it is called, on the turn.

I maintain that Berliner touched a certain aspect of the truth. In maintaining this and committing these notes to writing, I realize that I may be discrediting myself, and inviting suspicion of my other conclusions. Nevertheless, the danger which I call Danger B deserves investigation.

Doctor Sant’s F.S.2 is regarded as vastly important. Apart from that which makes it fly. There is an automatic air-compression device and a “forward brake”—as they call it. Work is going forward on F.S.3. Hahnigen’s lined duralumin will make practical Sant’s early dream of the double nose. Fower’s indicator will be foolproof, pressure-proof and altitude-proof. Weather permitting, F.S.3 should be tested in May, 1947.

That F.S3 will almost certainly break every known record is unimportant, as I see it. The War Department believes in Doctor Sant. So do I. Doctor Sant believes in the improbable: so did Galileo, Marconi, Watt, Leonardo da Vinci and the Brothers Wright. And so do I.

It is pretty well established that Dr. Sant never committed himself without reason. I cannot understand what Berliner wrote any more than a journalist of the eighteenth century could understand what Newton wrote, but I have faith in Sant—like the War Department.

The Sant Report may indicate that when it is safe to travel fast enough, we may have conquered death—that is to say, the ordinary physical and emotional wear and tear of life and time. It is indicated that if we move fast enough, we can catch up with past years.

I put this badly because it is necessary to convey the straight idea. Fine writing, imaginative writing—must come later.

I have the report of the Montana crash. Ted Oxen took off alone in a certain jet-propelled plane which crashed in Montana. Out of the scorched and twisted wreckage the authorities picked certain remains of a human being. This human being must have been a child nine or ten years old, according to the analysis of the carbonized fat. It remains to be worked out.

The End

And you cannot have some Saturday Evening Post without at least one commercial message from the time.

The pages of early Saturday Evening Post issues brimmed with richly painted scenes that went far beyond mere product pitches. These ads invited readers into crafted worlds—whether a cozy family kitchen, a sunlit countryside picnic, or a bustling city street—through color, narrative, and the unmistakable hand of an artist. They told stories with each illustration unfolding like a mini–short story, showing viewers how a product fit seamlessly into life’s moments: the proud father serving pancake batter, the glamorous hostess pouring soda for guests, or the rugged handyman using the latest tool. They shaped sheer desire through idealized figures and aspirational settings, artists tapped into readers’ hopes—comfort, elegance, adventure—and made a purchase feel like the key to that lifestyle. As photomechanical processes became affordable and faster, advertisers gravitated toward photographic realism.

Later, the precision and speed of camera-based ads gradually displaced hand-painted work. Yet this change also narrowed the realm of imaginative interpretation; photos could show you what something looked like, but only an illustration could imagine what owning it might feel like. James Hall